Tilley the Kid and I were sitting on the back balcony during a rare sunny interlude, drinking a cup of my mint and rosemary concoction, fresh from our weedy octagonal herb garden. Since she was working on her leafy mural – an ongoing project to turn our breakfast bar into a detail of Douanier Rousseau’s famous primitive painting of a jungle (a project which is beginning to take on the proportions of the Sistine Chapel) – she got to choose the music.

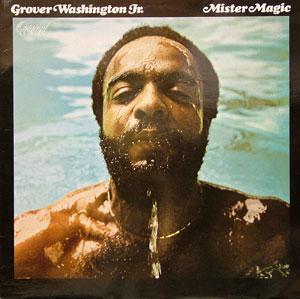

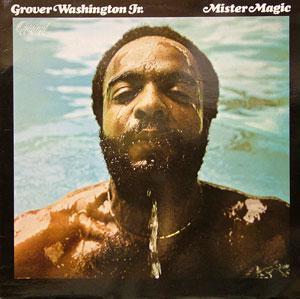

It was Amy Winehouse’s Frank, an album that I prefer to its more celebrated successor, Back to Black, and I recognised a tune that she or a collaborator put words to. It was ‘Mister Magic’. I nipped upstairs to find Grover Washington Jr.'s album of the same name, so I could play it to my girl as part of her compulsory musical education. A second airing in as many months surely qualifies an album now more than 40 years old as a ‘lifer’.

During my brief tenure in a hall of residence at Exeter University, Mister Magic was one of the records of choice in the corridors of soul-power. I first heard its funky beat thumping out of Mike Doherty’s king-size speakers. I knew from the way that my hips were moving to that crazy beat that I had to have it.

The second half of the '70s and a few years beyond were Grover Washington Jr.'s heyday. Many of his records, such as Feels So Good (the follow-up that also appeared in 1975), seem now to have one particular stand-out track that puts the other titles in its shade. Mister Magic may have only four, two per side, but what makes it exceptionally good is that the other three are almost as good as that wickedly insistent title track.

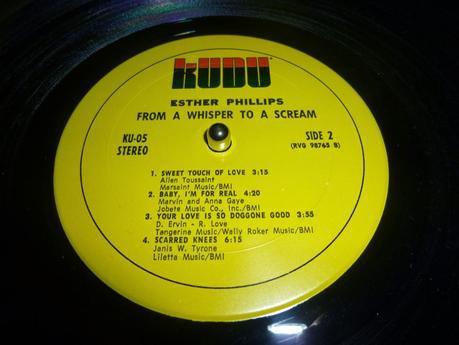

A tenor saxophonist from Buffalo, Washington had a beefy sound that recalls two minor luminaries of the ‘50s of whom I’m particularly fond: Ike Quebec and Gene ‘Jug’ Ammons. He found his niche on producer Creed Taylor’s Kudu label, which provided him with a rock-solid in-house rhythm section whose real stars were Harvey Mason on drums and Ralph MacDonald on percussion, both of whom would feature prominently on George Benson’s live double album of the era, Weekend in LA.

Like many a tenor man before and since, Washington doubled on soprano sax. And it’s the soprano that’s the main voice on the two opening tracks: keyboard player Bob James’s atmospheric ‘Earth Tones’, and ‘Passion Flower’, a beautiful tune written by Duke Ellington’s beloved collaborator, Billy ‘Swee’ Pea’ Strayhorn. An advisory sticker might have warned me that it employs a big string section. Normally I avoid them like a pandemic, but on this occasion strings enhance rather than trivialise the delicate melody.

That strings also appear on both tracks of Side 2 only goes to show that – like the best disco numbers – a bit of saccharine in your funk is not always the bad idea it might appear. The title track, otherwise, is a fabulous bit of straight ahead blowing, propelled by Harvey Mason’s knot-tight drumming and Eric Gale’s choppy funked-up guitar. A horn section’s insistent stabbing motif adds colour and oomph to what is arguably Washington’s career highlight.

It’s a difficult act to follow, but the moody ‘Black Frost’ makes a good stab at it. The strings on this occasion lend it an icy quality that wouldn’t be amiss in one of those gritty detective thrillers of the time, like The French Connection.

The whole caboodle was recorded at Rudy van Gelder’s famous studios in Hackensack, New Jersey, where the engineer-of-choice presided over countless great jazz sessions in the 1950s and 1960s – which helps place Mister Magic, I suppose, in the tradition of soul jazz and the groups led by the likes of pianist Horace Silver and alto saxophonist Lou Donaldson.

The Kudu label, however, was not to emulate Blue Note’s immortality. Synonymous with the fairly short-lived era of jazz-funk, at its worst the Kudu output was subject to the kind of ‘smooth jazz’ clichés characteristic of Bob James’s solo albums. Grover Washington was less guilty than some, but before he died prematurely of a massive heart attack, he was partly responsible for foisting Kenny Gee on vulnerable audiences everywhere.

At its best, though, Kudu helped to revitalise the career of Esther Phillips and to leave us with a legacy of albums like Mister Magic that bolstered commercial success with genuine musical substance. The label’s sax star from Buffalo would end up signing with Elektra and would continue to bring out popular albums, such as Winelight.

Personally, I had lost interest in him by then and moved on to things a little less smooth. Several of his Kudu albums sit on our shelves, but it’s only really Mister Magic that earns repeated airplay. I rather like what Amy Winehouse did to the song, but like even more that The Daughter seems to like the original. That’s my girl, getting on the good foot.