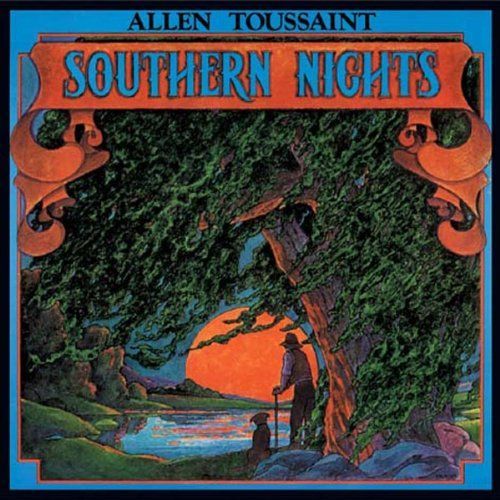

Southern Nights

Well, it’s the Toussaint holiday here in France: that

Well, it’s the Toussaint holiday here in France: that

dreary time of year when autumn is just starting to merge with winter and

families place chrysanthemums on the graves of their predecessors. And since my

November radio show is a tribute to the great singer, songwriter, pianist,

producer and generally gracious individual who left his native New Orleans roughly

a year ago for a celestial destination unknown, what more appropriate subject

for La Vie en Albums than Allen

Toussaint’s Southern Nights?

It’s a crying shame that his death wasn’t marked by a

special show to celebrate his life on the BBC. Only the cognoscenti appreciate

that this modest man, in terms of the history of black music, was every bit as

influential as Berry Gordy, Smokey Robinson, Gamble & Huff, James Brown and

others of their kidney. There may yet be a documentary on BBC Four, but then I

suppose the discreet charm of this delightful man wouldn’t have been quite so

discreet had he been as lauded as he deserved.

Even as a songwriter (although probably for contractual

reasons), he often hid his light under a bushel: as his alter ego, Naomi

Neville (his mother). Mr. Toussaint and/or Mrs. Neville wrote so many songs

that it’s almost impossible to log them. Even as a fledgling Music O’Phile, I encountered

him subliminally as the author/producer of Lee Dorsey hits that were

occasionally aired on Top Of The Pops.

‘Holy cow, what ya doin’ now?’ Working in

a coalmine, actually. Or sitting in la-la, waiting for my ya-ya.

No, clearly it wasn’t profound stuff. He was keeping that,

I should imagine, for occasional solo projects like Southern Nights and it’s only-marginally-inferior successor, Motion. But when it came to hit records,

my! could he churn them out. And the thing about the genres of New Orleans

rhythm & blues and soul that Allen Toussaint did so much to popularise is

that the lyrics are often little more than an excuse for that infectious,

quirky and quite unique rhythm.

Jessie Hill’s ‘Ooh Poo Pah Doo’ for example is pure

pounding onomatopoeia. If it’s still out there, you can find it among many

other mini masterpieces on a compilation released by the Charly label in the

late '80s: Mr. Joe’s Jambalaya. I

bought it as a cassette and duplicated it almost immediately in case anything

untoward should happen to it. Certainly it was never allowed anywhere near a

car, to risk being chewed and spewed by a cassette player.

The Mr. Joe in question is Joe Banashak, a local impresario

who founded Minit and a stable of tiny independent sister labels, for all of which

Toussaint became the sine qua non. He’s there as producer, songwriter and/or

session pianist on everything from Ernie K. Doe’s ‘Mother-In-Law’ to Irma

Thomas’s southern soul classic, ‘Ruler Of My Heart’, which Otis Redding would

modify to ‘Pain In My Heart’. And, although you won’t find them for some

inexplicable reason on this particular compilation, Mr. T. was also responsible

for Benny Spellman’s ‘Fortune Teller’ (to be covered by the Stones and a million

others) and, my personal favourite, Chris Kenner’s delirious ‘Land of 1,000

Dances’, which even knocks spots off ‘Wicked’ Wilson Pickett’s subsequent

classic.

After a stint in

the army, Toussaint teamed up with music publisher Marshall Sehorn to found the

Sansu organisation, which incorporated more boutique indie labels, for whom

Toussaint continued to play, write and produce. The customary common

denominator on records by the likes of the good Dr. John was a house band synonymous,

like Booker T. & the MGs up in Memphis, with some of the funkiest sounds

ever put down by a four-piece. The name of the eight-legged beast was The

Meters and it was via the Meters – and albums like Fire On The Bayou and

Rejuvenation – that I finally, at last, came to the shadowy maestro who

pulled the musical strings.

By the time Southern

Nights came out in 1975, as Toussaint’s third solo ablum, the Sansu team

had opened the Sea-Saint studios in New Orleans. Artists from far and wide were

now coming there in search of the magic touch: the Pointer Sisters, when they

were still a kind of retro black Andrews Sisters; that wonderful vocal trio,

the Mighty Diamonds, for a misguided attempt to blend reggae with Noo Orlinz

soul; the mighty Labelle, for the monumental ‘Lady Marmalade’; and a whole host

of disparate others, including Robert Palmer of all people. I heard the title

track of his Sneakin’ Sally Through The Alley LP at a small free

festival in a former graveyard near the centre of Bath and thought, I’ve got

to have this NOW! (unaware that it, too, was written by Allen Toussaint for

Lee Dorsey).

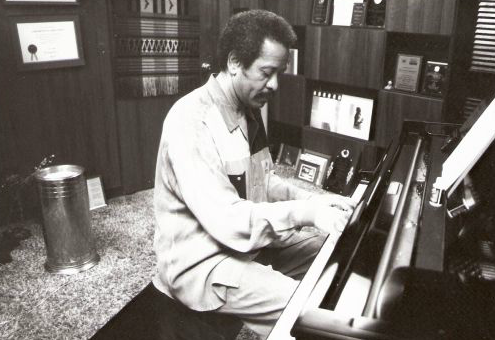

The modest Monsieur

Toussaint openly admitted to being much happier behind the scenes, which

probably explains why he produced so few albums under his own name. The irony

is that he had a lovely velvety tenor voice and could play the piano as fluidly

as his hero and R&B forerunner, Professor Longhair, and his contemporary

collaborator, Dr. John. He had the studio set-up, a coterie of finest local

musicians (including all four Meters) and, above all, he had the songs. The

mushy dame to whom I’m married only has to hear the song ‘Southern Nights’ and

she dissolves into jelly. She has never knowingly dissolved to Glen Campbell’s jauntier

hit version of the song.

Late of the Steve

Miller Band, Boz Scaggs picked the beautiful ballad on the same side of Southern

Nights as the title track, ‘What Do You Want The Girl To Do?’ to adorn his

hit album, Silk Degrees, just as he had picked on Aaron Neville’s fabulous

‘Hercules’, another Toussaint classic, for its predecessor, Slow Dancer.

Goodness me, it’s like a severe case of six degrees of separation. But then it

would be difficult not to

mention the name Allen Toussaint in the same breath as that of the music of New

Orleans.

Southern Nights

is replete with up-tempo funky numbers like ‘Basic Lady’ and the opening ‘Last

Train’, moody soulful pieces like ‘Cruel Way To Go Down’ and the memorable

ballads I’ve already cited. It also has the distinction of echoing its title

track before rather than

after its actual appearance, as a link between the penultimate and the final

track on the first side. It all adds up to probably the finest example of his

more personal and less commercial work.

One of those

commercial songs goes by the title of ‘Everything I Do Is Going To Be Funky’.

Everything he did was also marked by the kind of style and grace that anyone

who has ever seen the documentary Piano Players Rarely Ever Play Together

will appreciate. Although he never thought of himself as a performer, his

performance on-film suggests not only a superb pianist in his own right, but a

raconteur and educator able to illustrate so compellingly some of the otherwise

indefinable qualities that make New Orleans rhythm & blues so magical.

The Smiths’ ‘This

Charming Man’ might have been written with Allen Toussaint in mind and it’s no

accident that another cultured man, the soon-to-be ex-President Obama, had the

sense and judgement to award him the National Medal of Arts. How lovely that,

for once, such an accolade came in his lifetime. Two years later Allen

Toussaint died of a heart attack. He was ‘only’ 77, but what a packed and

creative life he led and what a legacy he left.