A couple of years before we moved to France, me and the Missus had the great good fortune to see Michel Petrucciani perform at the Brecon Jazz Festival. I’d read about the prodigious jazz pianist and the genetic brittle bone disease (osteogenesis imperfecta) that meant he would never grow more than three foot tall, but nothing prepared us for his appearance.

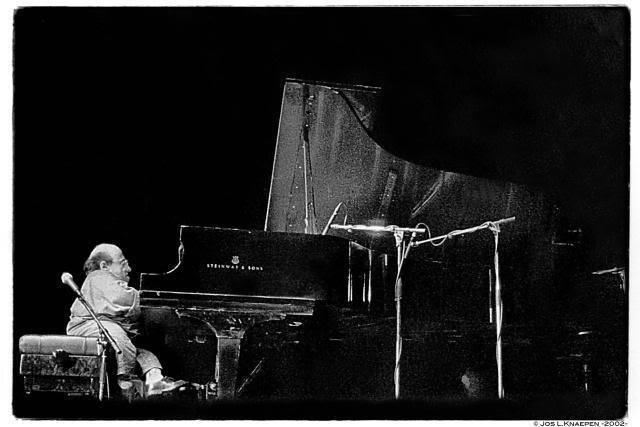

If memory serves me correctly, it was his bass player, Michael Bowie, who carried him on stage, holding in his arms this weird-looking infant-adult with outsize head and glasses, as his charge clung to his neck like a koala bear. We watched Bowie put him down and Petrucciani climb up onto his piano stool and adjust the pedal extensions that Steinway had made for him. He shuffled around on his seat to make himself comfortable, wished us ‘good evening’ and, for the next 90 minutes or so, he and his rhythm section played one of the most incredible sets I have ever witnessed. As chance would have it, the BBC recorded highlights for its short-lived Jazz from Brecon series, so we still have our video recording as a testimony to that evening in mid Wales.

On Friday evening, the two of us went to our local art et essai cinema to see Michael Radford’s captivating documentary on the French musical giant, who died in 1999 at the age of 36. Despite my efforts to drum up interest, the audience numbered the customary dozen or so, dotted around the cavernous steeply raked auditorium. The absentees missed a real treat.

In the years between Brecon and Vayrac, I’ve listened to just about everything Petrucciani ever recorded – including an astonishing solo concert recorded by Radio 3 from the Queen Elizabeth Hall, London – but I knew little about the man himself. Despite the temporary distraction of my initial guilt for dragging along a couple of Germans who couldn’t speak French (when I realised that, of course, there would be interviews with French as well as American people, and of course their words wouldn’t be sub-titled), Radford’s film was as riveting as the concert in Brecon.

Petrucciani sensed at a fairly early age that he wouldn’t be long for this world, and he crammed much more into his 36 intense years than most of us manage in a lifetime. His philosophy was ‘to have a really good time and never to let anything stop him from doing what he wanted to do. Encouraged by a musical Italian father, he started off playing drums, but then saw some TV footage of Duke Ellington and realised that he had to be a pianist.

He set about learning the instrument with the same intensity as he learned English when he travelled to America as a teenager. Within six months of settling in Monterrey – where his virtuosity and energy prompted the reclusive tenor saxophonist Charles Lloyd to perform in concert again – he could speak perfect vernacular American-English with little trace of a French accent.

In California he met and married the first of his three or four (I lost count) wives. This was quite a shocking and revealing aspect of the film: first the fact that so many women would fall in love with someone half their size, and then that Petrucciani – in his desire to keep changing and to keep renewing himself and thereby to keep experiencing as much as he possibly could – was able simply to walk away from the woman he loved (at the time) and to take up with the next person he took a shine to. But this is often what you find with artistic geniuses. On one hand, their creativity and their charisma makes them enormously attractive; on the other, their ruthless dedication to the artistic calling means that their muse is more important than anything or anyone else.

When he moved to New York, he found himself living in one of the most exciting cities in the world, mixing with some of the jazz greats he had previously only revered from afar – and not surprisingly he went haywire: playing constantly, sleeping too little, consuming too many drugs and generally doing everything to excess. Eventually he went back to Europe, leaving his second wife behind and taking up almost immediately with wife no. 3. When she found herself expecting a child, they were faced with the dilemma of whether to risk passing on his hereditary illness to a child. Petrucciani’s reasoning was that he wouldn’t have missed the chance of life for anything, so they went ahead. Sure enough, their son was born with the same brittle bones.

One of the most poignant elements of the film was the footage of his son, a young man who was, apart from his beard, the spitting image of his father. He talked of living in a world of giants and the pressure that his sense of being so different put on him to try to do something equally extraordinary with his life. Somehow you sensed that he probably won’t and that everything could, as a consequence, end in tears.

Another poignant aspect was the revelation of just what brittle bones means. Michel Petrucciani played the piano with such physical intensity that sometimes he would break a clavicle or some other bone in performance. When you listen to his long, sweeping, almost breathless improvisations, there is a sense of his driving himself through the pain barrier. Music must have been both a spiritual and physical balm.

After his years in Europe, where he recorded mainly for the Dreyfus label and with the likes of Stéphane Grappelli and where in 1994 he was awarded the Légion d’Honneur, he moved back to New York. But his lifestyle soon caught up with him and he died in the middle of a fearsome east coast winter after another night on the town. He was two years older than Charlie Parker before him, another burnt out case, another wayward musical genius, who lived the jazz life and pursued the muse with similar ferocity, who also kissed the girls and made them cry along the way. Like Jim Morrison, Michel Petrucciani is buried in Paris at the Père Lachaise cemetery. I think he had a better time in his life than the tormented ex-singer of The Doors did.

As I strapped on my safety belt and started up the Peugeot 107 after the film, I felt chastened by the little man’s remarkable legacy of 36 short years on this earth, but also heartened to recognise that there are certain advantages in living an ordinary life.