Thanks, interesting read.

I couldn’t access the article originally as it is behind a paywall but managed to get around it by posting the URL into here…

I get an “internal server error” when i try and use your proxy link , but thanks for having a go…

On the original topic, in 2018 I did a week’s tour of the Western Front battlefields with an Australian photographer friend of mine whose great-uncle fell on the Somme and is buried in a small Commonwealth cemetery near Amiens.

I found the whole experience very moving - almost overwhelming in fact - the emotional impact was such that I was glad we only spent a week on it instead of the two weeks originally proposed.

I can’t say I found inner peace from the trip but it was definitely worth doing, to understand the sheer scale of the suffering that WW1 combatants endured. WW2 was horrific too of course (especially for civilians) but the relentless “meat grinder” aspect of WW1 gives it a special horror.

It was also moving to see how well the French and Belgians look after the cemeteries of the War Dead, and how they commemorate the fallen.

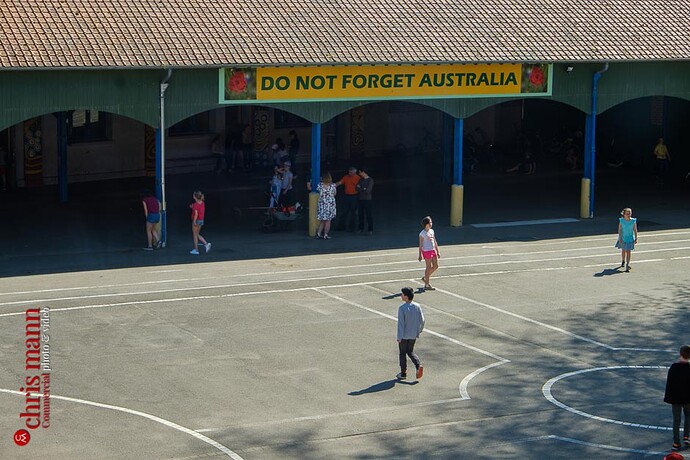

I’ve posted this before I think, but there is a school in the village of Villers-Brettoneux that was paid for by the citizens of Melbourne after the War, that still has a huge banner in the playground that says “Do not forget Australia”. And a bar in the main street is called “Le Melbourne”.

Canadian no. 2 cemetery at Vimy Ridge:

(modern) poppy tied to reinforcing bars on the remains of a German blockhouse at Fromelles:

The daughter of a Belgian friend works for the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and is currently the project manager for the Menin gate restoration project in Ypres

Me too ![]()

I was talking to a lady in the village this morning after the ceremonies at the war memorial and she was telling me about her grandfather who died at Verdun in 1914 a few months before her father was born. I told her we were planning on heading towards Bethune when we can in order to visit the grave of one of Gran’s two brothers who died in WW1. (The other didn’t have a grave).

My grandfather was too old to paticipate.

Yes my parents / grandparents were “the wrong age” for both World Wars, fortunately for our family!

Grandad was in the Boer War (2nd one I think) but Dad was in WW2. Because of his Mum losing her brothers in WW1, he was under a lot of pressure not to join the army, so joined the Navy instead (and survived!)

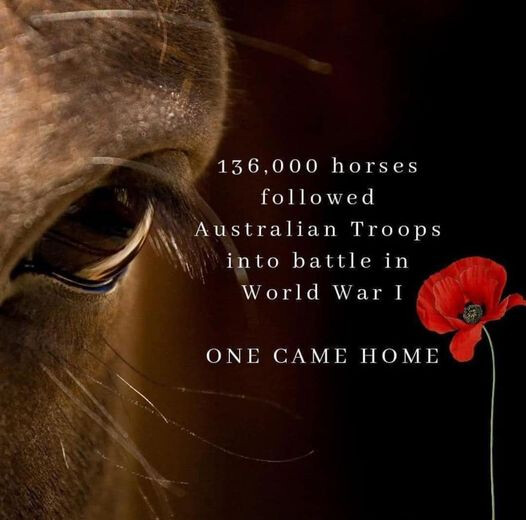

As you may know, there is a monument in London to the animals that served in war.

My father was a Bevan Boy in WW2 - he spent 1944/5 down a mine in Consett. It seemed to be the luck of the draw when you were called up - he had wanted to be in the RAF.

For someone claustrophobic & not physically tough it was hellish. He was not alone. Some of his colleagues would deliberately misbehave or not show up; the punishment was being sent into the army. Being shelled & shot at seemed preferable to working down a coal mine.

On Armistice Day I try to remember all of the death, pain & suffering that war created (& still creates) for everybody.

I suppose somewhat tangential to his thread, I’m really pleased to be going to the service at Les Invalides this afternoon. Despite not doing the god thing, I think it’s important to take the opportunity to remember.

My brother was the chief of works for the North of France from 96-99 then out to Israel for the CWGC but constant danger forced him to change direction and leave for another job.

Apologies, I incorrectly posted the wrong URL. I have edited my post so it should work now, you need to then paste the URL for the original article:

https://liveapp.inews.co.uk/?article=page-4323154&edition=lifestyle

I can’t read it I’m afraid, but I’ve toured (wrong word, but you know what I mean) the battle sites and cemeteries on a couple of occasions. The scale is overwhelming.

I was chatting with my neighbour this morning and he mentioned again how he had lost both his grandfathers in 1916, and how his father had “disappeared” into the maquis for four years of his early childhood, visiting home only rarely and unbeknownst to the children at dead of night.

I think many people, including politicians, take peace for granted and don’t realise just how quickly things can unravel.

Did you get to meet the PM for Breakfast?

Thanks for that. I had no idea…

Next time in London I shall look it up.

Yes it’s worth a look.

It’s in Park Lane, on what is essentially the central reservation of the dual carriageway, opposite Speaker’s Corner in Hyde Park and a short walk down from Marble Arch Tube station.

This is tangential too but these posts triggered me to have another look at where Gran’s brothers died. I’ve always known where Uncle Fred’s grave was in Noeux-les-Mines but I thought Uncle Bill didn’t have one. However, I’ve now not only found it, I’ve seen the headstone on Google Streetview and have a picture.

Next year we are heading to Magnaboschi…

My wife and I have visited many CWGC cemeteries in France and Belgium over many years. It was during one trip that we located my wife’s grandfather’s grave in a village cemetery in Belgium. My wife’s mother never knew where her father had been buried until we told her of our discovery. Later we discovered he had been killed, late at night, on the 10th November 1918 just hours before the war ended. A copy of the Unit’s diary we obtained showed that he had been carried to the church very close to where he fell and buried in the cemetery the next day. He lies with seven others in an imaculately maintained arc of GCWC headstones, just inside the cemetery gates. I never discovered why these eight bodies were not moved to a larger cemetery as was usually the case.

.

Here’s the article

The Western Front Way traces the First World War front lines for more than 1,000km (Photo: Ben Eley)

I am beckoned inside a peaceful haven of pristine lawn, pretty perennials and row upon row of uniform headstones. A Great Warstone watches over; a fabulous heft of Portland stone whose symbolism is not lost to superfluous ornament. The only words read: “Their name liveth for evermore’’.

I am at Dud Corner Cemetery, just outside the northern French city of Lens on the Western Front Way (WFW), the world’s largest active commemoration project and Europe’s latest pilgrim trail.

It traces the First World War front lines for more than 1,000km (621 miles) from the Belgian coast past poetic Flanders fields, the vines and forests of Champagne-Ardenne and over the Vosges to Alsace-Lorraine.

On the 130km (81-mile) stretch from Armentières by the Belgian border to Albert, the path is traversable on foot in a week, passing places etched in our national story.

One of Dud Corner Cemetery’s commemorated fallen lieutenants, Douglas Alexander Gillespie, is the reason behind this trail.

In a valedictory 1915 letter, Gillespie wrote, “When peace comes, our government might combine with the French Government to make one long avenue between the lines. I would like to send every man, woman and child in Western Europe on a pilgrimage along that Via Sacra so that they might think and learn what war means from the silent witnesses on either side.”

Weeks later, Gillespie was dead – but his dream of a Via Sacra was realised by WFW visionary Sir Anthony Seldon, who discovered the letter 100 years after the earliest “Great War” battlefield pilgrimages.

Conceived as a “path to peace”, tranquility awaits on the WFW in little-trodden Hauts-de-France. This agrarian heartland is timeless, bucolic France – farm tracks, country lanes and fields teeming with water reeds, wildflowers, monarch butterflies and bird song. Yet the war is inescapable. Stages roll-call Britain’s war effort, while sleepy villages, towns and gentle hills belie their terrible significance.

The military cemetery at Fromelles is particularly moving. The Pheasant Wood resting place was created after the 2008 discovery of mass graves of 250 fallen soldiers here. The horrors of the earliest trench warfare are laid bare in the adjoining state-of-the-art museum.

Two hours south-west at Neuve Chapelle, I find peace. The India Memorial on the outskirts of town is an infinity circle sanctuary, guarded by stone tigers under the boughs of the enlightened Nirvana Tree. More than 1.3 million Indian soldiers fought in the war, the country’s contribution the most widespread and one of the largest in the Commonwealth.

The Vimy Memorial (Photo: Ben Eley)

Lens is around four hours’ walk south, where I happily pause for a carb recharge with speciality double-fried frites (nearby Arras hosts the French Fries World Championships each autumn). The city is an emerging culture-hub with its Paris offshoot Louvre-Lens. But I push on into a landscape of slag heaps of Europe’s largest coalfields, now transformed into grassy ridges.

On the hill of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette is the sublime Ring of Remembrance memorial, an elliptical ring of bronzed stainless steel plates presented like an open book. Along its spur, Lens 14-18 offers one of the best explorations of the war.

The Vimy Memorial nearby is a monumental lamentation striking for the celestial skies, whose allegorical sculpture is accompanied by “Canada Bereft”: a peace poem in stone.

By the time I reach Arras, I’ve visited 30 Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) cemeteries and memorials. The CWGC maintains 23,000 memorials worldwide. Like outdoor cathedrals, they vault with the infinite skies, their designs an homage to eternal human values.

Thiepval memorial (Photo: Ben Eley)

Arras has layers. Its stunning squares are some of France’s largest, whose pretty rhythm of Flemish Baroque terraces host vibrant café culture. I then dive into the eerie Wellington Tunnels to sense the visceral subterranean war.

It is at the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme that I crumble. Its monumental proscenium arch is drenched in melancholic pride as I pay personal respects to Albert Lisle – my great-great-great uncle – one of 74,000 missing names whose remains, in Rudyard Kipling’s words, are ‘‘known unto God’’.